The Disappearance of the Indus Valley People—Climate Change, River Shifts, or Something Stranger?

September 2025 - J.M. Stokes

Ruins of Mohenjo-daro, an Indus Valley city — Credit: Saqib Qayyum, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Four thousand years ago, long before Rome rose or the Great Pyramids weathered desert winds, a sprawling civilization thrived along the Indus River plains. The Indus Valley Civilization—sometimes called the Harappan civilization—was among the world’s first great urban societies. Its cities were laid out with geometric precision, boasting drainage systems more advanced than many European cities had until the 19th century. Its artisans crafted exquisite jewelry, seals, and pottery. Its farmers cultivated wheat, barley, and cotton, feeding populations that may have reached five million.

And then, around 1900 BCE, it all faded. Cities were abandoned. Trade networks collapsed. The people scattered into villages. Unlike the Romans, who left behind a clear record of decline, the Harappans vanished from history with startling quietness. Why?

The Mystery of Collapse

Scholars have puzzled over this disappearance for decades. Unlike Mesopotamia or Egypt, the Indus Valley people left no deciphered texts to explain their fall. Their script—etched onto seals and pottery—remains undeciphered, leaving archaeologists with pottery shards, ruined streets, and ancient bones as the main storytellers.

Three major explanations dominate the discussion: climate change, the shifting of rivers, and cultural upheaval. But some researchers—and mystery enthusiasts—have wondered if there’s more to it than the slow grind of natural forces.

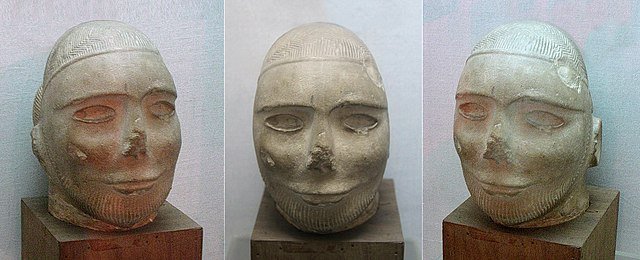

Limestone head from the Indus Valley Civilization — Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Theory One: Climate Change

Paleoclimate studies suggest that around 2200–1900 BCE, the South Asian monsoon system weakened dramatically. The lifeblood of the Indus civilization was seasonal rainfall, which fed crops and replenished rivers. A century or more of weakening monsoons could have meant crop failures, famine, and mass migration.

Evidence from lake sediments and cave formations in India indicates that this was not a small fluctuation but a long-lasting drought. Urban centers such as Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, heavily reliant on agricultural surplus, may simply have become unsustainable. The pattern mirrors other great collapses: the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia and the Old Kingdom in Egypt also faltered around the same time, suggesting a global climatic event.

Theory Two: Shifting Rivers

The Indus cities were built around powerful rivers—the Indus itself and its tributaries, including the now-vanished Saraswati (sometimes identified with the Ghaggar-Hakra). Geological surveys reveal that tectonic shifts and sediment buildup altered river courses dramatically around 2000 BCE.

If the Saraswati dried up and the Indus shifted westward, entire agricultural and trade systems would have collapsed. Imagine a metropolis like New York suddenly losing the Hudson River—it would wither in decades. Archaeological mapping shows once-thriving cities sitting along what are now dry riverbeds, lending weight to this theory.

Theory Three: Invasions or Cultural Change

Older generations of historians once blamed the “Aryan invasion”—a supposed mass migration of Indo-European-speaking tribes that swept into the subcontinent. This theory, popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries, painted a dramatic picture of conquest.

Modern archaeology, however, suggests no sudden wave of violence or destruction. The cities don’t bear the scars of fiery collapse; they appear to have been abandoned gradually. What may have happened instead was a slow merging: the Harappans drifting into rural life while Indo-Aryan culture spread over centuries, eventually shaping Vedic India. Rather than violent conquest, it might have been cultural diffusion, the old ways dissolving into new.

Or Something Stranger?

Here’s where the story tilts into the unknown.

Some researchers point out that the Indus script’s undecipherability is suspicious. Was it a true writing system or something more symbolic, like heraldic signs? If it was indeed writing, the loss of such knowledge hints at a profound societal rupture. Others point to the eerie uniformity of Indus artifacts—seals, weights, pottery—suggesting a highly centralized control system. Did internal political collapse play a role?

There are even fringe theories: ancient pandemics wiping out populations, catastrophic floods submerging cities (Mohenjo-Daro sits on layers of silt that some interpret as flood deposits), or astronomical events disrupting agriculture. A few enthusiasts, leaning into the mysterious, wonder if outside intervention—extraterrestrial or otherwise—might explain the civilization’s advanced planning and sudden disappearance.

Mainstream archaeology is cautious with such ideas, but the allure of “something stranger” lingers. After all, this was a society that built without obvious kings or palaces, with no massive temples or royal tombs. Was it a civilization structured in a way fundamentally different from any we know? And did that uniqueness contribute to its vulnerability when crisis struck?

What Happened to the Indus Valley Civilization? via YouTube